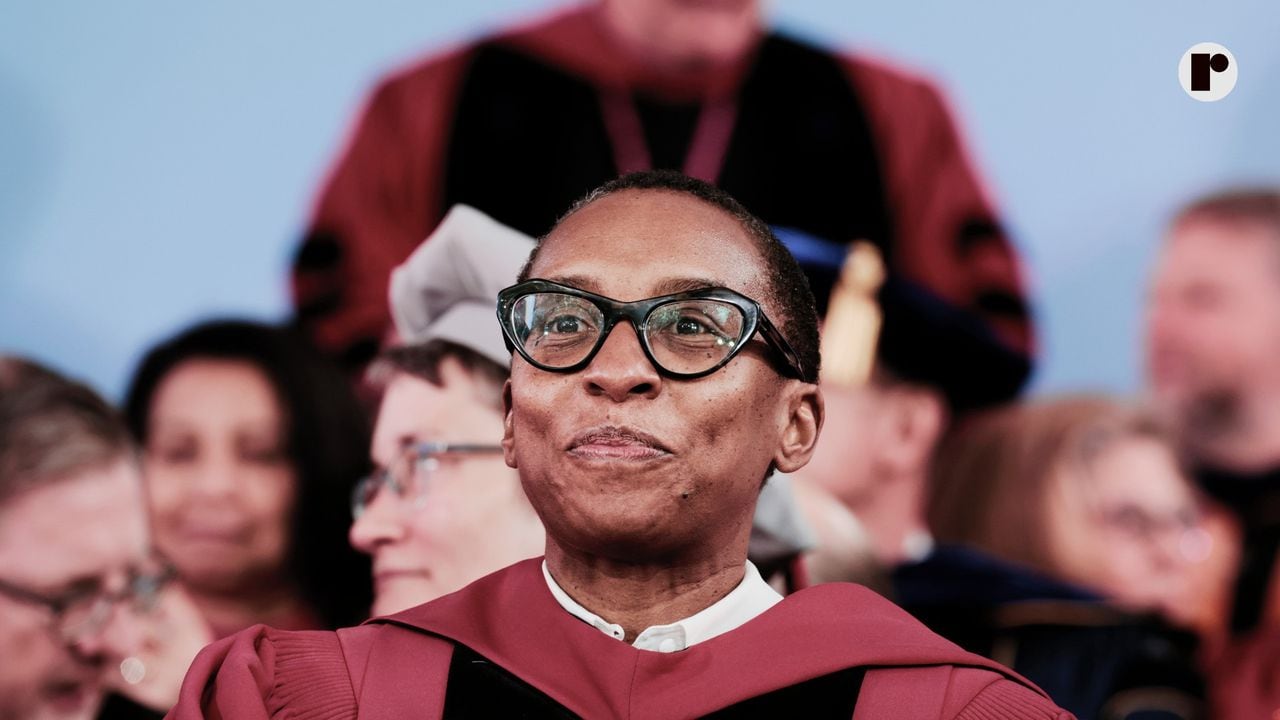

Inside Claudine Gayâs resignation and the hyper scrutiny haunting Black women in higher ed

On Jan. 2, former Harvard University president Claudine Gay resigned from her position. She was the second woman and first person of color to serve as president in the university’s 386-year history. People called for her resignation due to accusations of plagiarism and anti-semitism.

Some individuals like conservative activist Christopher F. Rufo celebrated Gay’s resignation online.

“This is the beginning of the end for DEI in America’s institutions. We will expose you. We will outmaneuver you. And we will not stop fighting until we have restored colorblind equality in our great nation,” Rufo said in a Jan. 2 tweet.

However, Black women in higher education like racial, social and gender justice educator Ericka Hart, who was previously fired from Columbia University in 2020 for raising concerns about a student’s comments, are calling out the discrimination and racism behind the pressures Gay had to endure.

“We (Black and non Black people of color) have to really sit with how these institutions do not give two s**** about us and will see us out expeditiously if we do not follow their white supremacist agenda,” Hart said in a Jan. 4 Instagram post.

Other Black female administrators and professors in higher education as well are now posting and speaking about the extreme pressures they have also faced in these positions compared to their white counterparts.

The impact of Gay’s resignation

Gay’s resignation due to outside pressures is more than just a Black woman leaving a position of power to those on social media.

“I just want to make it plain that Harvard has had blatantly racist white Presidents/faculty and students and NOTHING was done. NOTHING. The fact that the school is still celebrated despite its history is grotesque. This happens across higher education,” Hart said in her Jan 4. Instagram post.

For Cal Poly Pomona professor and former provost Dr. Jennifer Brown, Gay’s resignation made them deeply saddened about the struggles she knows she has gone through.

“I really have no words to describe how it feels to get to a certain point in your career and to have it be so short lived, due to circumstances outside of your control. I could just say that I know firsthand when you are targeted for something the impact it has on your mental health or on your physical health,” Dr. Brown said.

These struggles and racial disparities in higher education can also be seen when looking at the statistics of tenure. A 2021 data set from The U.S. Department of Education found that tenured Black women only made up 2.8% of tenured faculty at U.S. universities.

“Black women experience institutional barriers at every stage of the academic process, starting with admission into graduate programs, yielding a small pool of credentialed graduates available for tenure-track faculty positions. Then the tenure process further culls the herd,” Boston University Associate Dean of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Malika Jeffries-EL said in a 2021 BU Today article.

Some of these barriers include “microaggressions from faculty and students, invalidation of their research, and the devaluation of their service contributions in the tenure process,” a 2021 article from Inside Higher Education states.

Once Black women make it on track to be considered for tenure, their research can face higher criticism, especially if it focuses on other Black people, according to the article. If they make it through all of that, colleagues can question how they made it into the department in the first place.

How hyper scrutiny affects Black women

The issues that Black women have been facing in higher education are nothing new, as seen in a report from the University of Colorado Boulder in 2020.

In the document, two Black female graduate students interviewed former female faculty members from the university to learn about their experiences. Unfortunately, they were more negative than positive, especially for Black female faculty.

“The University of Colorado Boulder has a continual history of rampant and unbridled anti-Blackness. The systematic bullying, denigration and surveillance of women of color faculty, and Black women faculty, in particular, was excessive, obvious and undeniable,” the document stated.

Policies are in place at certain universities that can cause other Black women to feel as if they have a negative spotlight. For example, Angela Onwuachi-Willig currently serves as the Dean of the Boston University School of Law. Nevertheless, she has said that she has been looked down on due to having a locs hairstyle.

“What’s troubling is that banning these hairstyles essentially tells Black girls and women — nearly all of whom have tightly coiled hair or coiled hair that grows into an Afro — that the hair they were born with is faddish, extreme, distracting, and unprofessional,” Onwuachi-Willig said in a interview for a 2017 Berkeley Law article.

On top of having their appearance scrutinized, the qualifications of Black women can be questioned by their colleagues or others as well, despite the positions they may hold.

In the classroom, Hart says that she has had “students complain about their grade and demean the fact that I do not have a Ph.D. so ‘what could I possibly know about teaching,” in a 2021 interview with Forbes.

Despite the push in society for more diversity and inclusion, some Black women in higher education feel as if they are the “token hire” at their university. A 2015 study found that Black women “appointed to serve as a college/university president are continuously challenged and denied by their governing board at every impasse.”

They have to serve as the representative of their whole community, causing them to be seen as “symbols” and impacting their growth in their career.

Attending predominantly white institutions in the past, Colorado College Associate Professor of Education Manya C. Whitaker knew how it felt to be the only Black person in the room. However, working as faculty, she was unprepared for the to be the “default expert on all things related to race/power/privilege, the contact person for the low-income school district, the assumed mentor for BISOC, nor the automatic supervisor for theses about anything ‘diversity-related,’” she wrote in her 2021 essay “When the Teacher is the Token: Moving from Anti-Blackness to Antiracism.”

This treatment can lead to feelings of isolation and invisibility in the social settings of white academia that they must participate in. Even though Black women “are accounted for and visible when it comes to statistical reporting; however, they are discounted or deemed invisible when it comes to intelligence or academic ability,” the study states.

Having to endure these conditions can cause more than just stress. The 2022 book “We’re Not OK: Black Faculty Experiences and Higher Education Strategies” found that the discrimination that Black faculty can face in these positions can cause mental health conditions like depression and anxiety.

“I have had more health problems from this past job with the mental stress, the sleepless nights and going from being successful with every single venture to now second guessing who you are as a leader due to targeted hate,” Dr. Brown said.

What needs to change in higher education

From Dr. Brown’s point of view, higher education needs to be reset. Nevertheless, universities are opening up soon from winter break, making her curious about what’s to come from programs like Harvard.

“We need to get back to a place where there can be a difference in opinions, respectfully. We’re thinking about how to create and generate new knowledge with respect to the status of African Americans, women, and marginalized communities,” Dr. Brown said.

Gay in a Jan. 3 opinion piece for the New York Times offered a similar message to readers, writing a warning to those in higher education and beyond.

“At tense moments, every one of us must be more skeptical than ever of the loudest and most extreme voices in our culture, however well organized or well connected they might be. Too often they are pursuing self-serving agendas that should be met with more questions and less credulity,” Gay said.